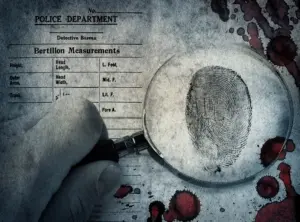

This part delves deeper into how Locard’s Exchange Principle and Bertillon’s work continue to influence modern investigations, even if Bertillonage itself is no longer the gold standard for identification.

Locard’s Exchange Principle: The Foundation of Trace Evidence Analysis

Step into a crime scene – a ransacked room, a shattered window, a trail of seemingly invisible traces left behind. Here’s where Locard’s Exchange Principle, formulated in the early 20th century, takes center stage. This foundational principle states: “Every contact leaves a trace.” During a crime, an inevitable exchange occurs. A perpetrator might leave behind a single hair snagged on a windowsill, or a microscopic fiber from their clothing. A homicide suspect might transfer a bloodstain invisible to the naked eye. Locard’s genius lay in recognizing the potential hidden within these seemingly insignificant traces.

Fast forward to today’s high-tech crime scene investigations. CSIs meticulously collect every piece of evidence they can find – hair, fibers, bloodstains, skin flakes, even dust particles. These seemingly insignificant traces are then analyzed in sophisticated laboratories using techniques like microscopy and DNA analysis.

The Power of Trace Unveiled: A Hair Can Speak Volumes

Consider a single hair found at a crime scene. Microscopic analysis can reveal its origin – human, animal, or synthetic fiber. DNA analysis can link the hair back to a specific individual, a crucial piece of the puzzle in a criminal investigation. Similarly, a single fiber found on a suspect’s clothing can be traced back to a specific garment found at the crime scene, potentially placing the suspect right in the heart of the action.

Beyond Fingerprints: A Rich Tapestry of Evidence

While fingerprints remain a cornerstone of forensic identification, Locard’s Exchange Principle has opened the door to a vast array of trace evidence analysis. Imagine a bloody fingerprint found at a crime scene. Fingerprint analysis can identify the perpetrator, but DNA analysis of the blood can provide a wealth of additional information. It can reveal the victim’s identity, narrow down the timeframe of the crime, and even identify the presence of any potential diseases.

Yes, the core information about DNA analysis is scientifically accurate. Here’s a slightly revised version for even better precision:

Decoding the Fingerprint of Life: A Deeper Look at DNA Analysis

For the reader familiar with the concept of DNA evidence excluding or including suspects, here’s a closer look at the mechanics behind this powerful technique. DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is the hereditary material found in nearly every cell of our bodies. It carries our genetic code, a unique set of instructions that determines our physical traits and even some predispositions to diseases.

Forensic DNA analysis hinges on targeting specific, highly variable regions of this code known as Short Tandem Repeats (STRs). These STRs are like microsatellites, consisting of short sequences of nucleotides (adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine) repeated a varying number of times. The number of repetitions at each STR locus (location) differs between individuals, creating a unique DNA profile. Forensic analysis focuses on identifying these variations at multiple STR loci to establish a DNA profile for a suspect or crime scene sample.

By comparing the suspect’s DNA profile to the crime scene profile, analysts can determine if the suspect’s DNA matches the evidence. A statistically significant match provides strong evidence linking the suspect to the crime scene, while a lack of concordance at multiple STR loci effectively excludes the suspect from further investigation.

The Enduring Legacy of Bertillonage: More Than Just Mugshots

While Bertillonage, with its reliance on body measurements, is no longer the primary method of identification, some aspects of Bertillon’s work continue to be relevant in modern forensics.

- The Importance of Meticulous Record-keeping: The foundation of Bertillonage was a detailed and organized record-keeping system. Today, meticulous documentation of evidence, crime scene photographs, and suspect information remains a crucial aspect of any forensic investigation. Imagine a complex legal case hinging on a misplaced fingerprint or a missing fiber sample – proper record-keeping ensures the integrity of the evidence and provides a clear chain of custody.

- Facial Reconstruction: A Legacy Lives On: The techniques Bertillon developed for capturing facial features in his identification system are still used today, albeit in a more sophisticated way. These techniques play a vital role in facial reconstruction efforts for unidentified remains or forensic facial composite sketches used in suspect identification.

A Tapestry Woven Together: The Interplay of Techniques

Locard’s Exchange Principle, fingerprint analysis, and the legacy of Bertillonage’s emphasis on record-keeping all come together to create the robust forensic science system we rely on today. No single technique exists in isolation.

Imagine a complex tapestry, each thread representing a different element of forensic science. Fingerprints might be the vibrant central motif, but the intricate details – the trace evidence analysis, the meticulous record-keeping – are what provide context and strength to the overall picture. A single fingerprint might not tell the whole story, but when combined with trace evidence analysis and a well-documented chain of custody, it can paint a compelling picture for the courts.

The Future of Forensics: A Continuously Evolving Landscape

The field of forensics is constantly evolving. New technologies are emerging all the time, allowing for the analysis of even smaller and more sophisticated forms of trace evidence. DNA analysis techniques are becoming more refined, offering the potential to identify not just individuals but also specific subpopulations or even ancestral origins.

A Legacy of Innovation: Paving the Way for Modern Forensics

While the days of Bertillonage and its meticulous measurements are long gone, the work of both Locard and Bertillon laid the foundation for the scientific approach to criminal investigation we use today. Locard’s Exchange Principle continues to guide crime scene investigations, reminding us that even the most insignificant trace can hold the key to solving a crime. Bertillon’s emphasis on detailed record-keeping ensures the integrity of the evidence and provides a crucial historical record for future investigations. Theirs is a story of innovation, competition, and ultimately, a shared pursuit of justice through science.

The Ever-Expanding Universe of Forensics

The field of forensics is a constantly evolving landscape. New technologies are emerging all the time, allowing for the analysis of even smaller and more sophisticated forms of trace evidence. DNA analysis techniques are becoming more refined, offering the potential to identify not just individuals but also specific subpopulations or even ancestral origins. For example, advancements in DNA analysis are allowing scientists to perform low copy number (LCN) DNA analysis, which can be crucial in cases where only a minute amount of biological evidence is available, such as a single hair or a touch sample.

The Future of Forensics: A Collaborative Endeavor

The future of forensics lies in collaboration. Forensic scientists from various disciplines – biology, chemistry, toxicology, digital forensics – work together to create a comprehensive picture of the crime. Imagine a team effort where the biologist analyzes hair samples, the chemist identifies the composition of an unknown substance found at the scene, and the digital forensics expert recovers deleted files from a suspect’s computer. By combining their expertise, they can paint a much richer and more detailed picture of the crime scene.

A Legacy that Endures

Locard and Bertillon, despite their differing approaches, stand as testaments to the power of scientific thinking in criminal investigation. Their work, along with the continuous advancements in forensic science, has led to a system that strives to uphold justice with ever-increasing accuracy and objectivity. The future of forensics holds immense promise, with new technologies and collaborative approaches offering the potential to solve even the most complex crimes. The legacy of Locard and Bertillon ensures that the pursuit of truth through science remains at the forefront of criminal investigations.

Part 3 is just around the corner – thanks for reading and we’ll see ya next time!