Finding the Balance

Why Charismatic Leadership is Key, but Autocratic Leadership Still Has a Place in Law Enforcement

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution establishes a robust protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, particularly within the sanctity of one’s home. Absent a warrant—supported by probable cause and judicial approval—government intrusion into private dwellings is presumptively impermissible.

Death investigations, however, often present unique challenges, as fatalities frequently occur within private residences rather than public spaces. Despite this, no categorical “death investigation exception” exists to circumvent the warrant requirement. The Supreme Court has consistently underscored the heightened protection afforded to homes, rendering warrantless entry a rare and narrowly circumscribed exception.

Certain exigent circumstances may justify immediate police action without prior judicial authorization. Consider a scenario involving a report of a possibly deceased individual in a residence, accompanied by evident signs of violence or distress—bloodstains or an unsecured weapon, for instance. In such cases, officers may enter to address imminent threats, such as a potential assailant still present or an injured party requiring aid. These exigent circumstances temporarily suspend the warrant obligation, permitting officers to stabilize the scene.

The “emergency aid doctrine,” allows entry when officers possess an objectively reasonable basis to believe an individual inside is in immediate danger. For example, audible cries for help or credible witness reports of a struggle may suffice. However, this authority is strictly limited: once the emergency is resolved, further investigative actions—such as a comprehensive search or evidence collection—require a warrant or an alternative legal justification.

Once the scene is stabilized, what do you do? Hang around? Rummage through the trash incase an injured party is hiding in the kitchen trashcan? Remember, your actions will be scrutinized under the reasonable officer standard later. You really only have two valid options: obtain consent from a person with standing or exit and apply for a warrant.

Law enforcement may occasionally invoke the “community caretaking” doctrine, which permits officers to act in a protective capacity distinct from criminal investigation. In the context of a death—such as a landlord discovering a deceased tenant—this doctrine might be cited to justify entry for public safety or welfare purposes. However, the Supreme Court’s 2021 decision in Caniglia v. Strom decisively curtailed this rationale. The Court held that community caretaking, while applicable to public settings or vehicle-related incidents, does not extend to warrantless entries into private residences. Thus, absent an immediate emergency or explicit consent, this doctrine provides no foothold for police in death investigations.

An unambiguous exception arises when an individual with lawful authority over the premises—such as a cohabitant or property owner—voluntarily consents to police entry. This permission, provided it is free from coercion or deceit, effectively waives the warrant requirement. The legitimacy of consent hinges on the authority of the granting party and the absence of undue influence, rendering it a straightforward yet potentially critical avenue for lawful access.

When a death shows hallmarks of criminality— gunshot wounds, stab marks, or other indicia of foul play—the investigative dynamic shifts. Such circumstances may establish probable cause, enabling officers to secure the scene to prevent evidence loss. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Mincey v. Arizona (1978) clarifies that even in homicide cases, the presence of a corpse does not inherently authorize a full warrantless search. Beyond initial stabilization efforts, further exploration of the premises necessitates judicial approval unless an exemption persists.

Death investigations often defy clear categorization. An apparent overdose, for instance, may raise questions of accident versus intent, yet without overt signs of emergency or consent, officers lack authority to enter and collect evidence such as pharmaceuticals. Similarly, a “suspicious death” lacking tangible indicators—blood, weapons, or disruption—does not automatically justify intrusion. In such instances, probable cause or consent must be established; mere intuition is insufficient.

In summary, law enforcement generally requires a warrant to enter a residence during a death investigation, save for narrowly defined exceptions: exigent circumstances, emergency aid, or voluntary consent. The Fourth Amendment remains unwavering. It is not affected by the violence that may have taken place within the walls of the home. Precedents such as Caniglia v. Strom and Mincey v. Arizona reinforce this principle, permitting warrantless action only when immediate necessity or explicit permission prevails. For officers, this mandates a careful balance—prompt response to genuine threats must coexist with respect for constitutional boundaries, lest judicial review overturn their efforts.

Why Charismatic Leadership is Key, but Autocratic Leadership Still Has a Place in Law Enforcement

Imagine a world where hunches and shaky witness testimonies held more sway than cold, hard evidence. That was the reality of criminal investigation for much of history.

The integration of drones, also known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), into law enforcement operations has sparked a revolution in policing, offering a plethora of benefits that enhance public safety and transform investigative techniques.

Strangulation is a type of mechanical asphyxia, which can result in death or permanent disability. Non-fatal strangulation is a increasingly recognized form of domestic violence.

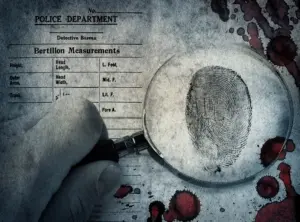

For the seasoned reader steeped in forensic history, the names Bertillon and Locard evoke a fascinating turning point. While Bertillonage, with its intricate anthropometry, may seem quaint compared to modern forensics, its legacy is far from forgotten.

Get discounts on training, free gear and training, news and training announcements.

Get free bi-weekly law enforcement training articles and a discount on your next session. Plus, snag a free guide: “Top 10 Deadly Mistakes of Suspect Interviews.”

Sign up now! 🌟